Self-Hosted GitHub Actions Runners: When Free Minutes Run Out

Running out of free GitHub Actions minutes? Here's how to set up your own self-hosted runner for unlimited CI/CD workflows.

Self-Hosted GitHub Actions Runners: When Free Minutes Run Out

It happened to me too, one night a few months ago: I was working on a personal project with a fairly large monorepo. Every push triggered Docker builds, tests, and deployments. Everything was going smoothly until around 2 AM when I noticed GitHub Actions had stopped. Out of minutes. Build stuck halfway. And there I was, needing to push an urgent deploy.

That’s when I realized I needed a solution. And I found it: self-hosted runners.

🎯 The Problem: Limited Free Minutes (And My Real Case)

GitHub Actions is fantastic, truly.

But let’s be honest: when working on private projects, the free tier limits hit sooner than you think:

- Public repos: Unlimited minutes (perfect!)

- Private repos: 2,000 minutes/month on the free plan

- Team plan: 3,000 minutes/month

- Enterprise: 50,000 minutes/month

In my case, I had a monorepo with several services.

Every push triggered:

- Builds for 3-4 Docker images

- Complete test suite

- Deployment to staging environment

Quick math: about 8-10 minutes per workflow. With 5-6 pushes a day (active development), that’s 50 minutes daily. In a month? Over 1,500 minutes. And that’s without counting rebuilds for urgent fixes.

Recently, I started experimenting with GitHub Copilot’s agent mode for some projects. While it’s incredibly powerful for automating development tasks, I quickly realized it consumes runner minutes too — and not just a few. The agents run on your GitHub Actions runners to execute their tasks, which can add up fast. If you’re already pushing your minute limits with regular CI/CD, adding Copilot agents into the mix might tip you over the edge, leaving you without minutes for your critical deployments.

The good news? You can use your own server to run GitHub Actions workflows — completely free, no minute limits, and you’re in full control.

💡 What Are Self-Hosted Runners?

Think of GitHub’s hosted runners as renting a car: convenient, but you pay per mile.

Self-hosted runners are like owning your own car: upfront cost, but unlimited usage.

For example, I have a small VPS that I was already using for other projects. I configured it as a runner and now I use it for:

- Building Docker images (which took 4-5 minutes each on GitHub-hosted)

- Integration tests that access a local database

- Automatic deployments to my servers

GitHub-Hosted vs Self-Hosted

| Aspect | GitHub-Hosted | Self-Hosted |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Metered (free tier limits) | Your hardware/cloud costs |

| Setup | Zero — just use it | Requires configuration |

| Maintenance | Fully managed by GitHub (OS updates, security patches, tools) | You manage everything (updates, patches, security, tools) |

| Infrastructure | Azure VMs managed by GitHub | Your own servers/VMs/cloud instances |

| Customization | Limited | Full control |

| Scaling | Automatic | Manual (or scripted) |

| Security | Isolated, GitHub-managed | Your responsibility |

| Speed | Good | Potentially faster (local network) |

Important: GitHub-hosted runners run on fresh virtual machines in Microsoft Azure that are automatically provisioned, updated, and destroyed after each job. With self-hosted runners, you are responsible for all operating system updates, security patches, tool installations, and general maintenance.

When Self-Hosted Makes Sense ✅

In my case, I chose self-hosted for these reasons:

- High CI/CD usage: I was constantly exceeding 2,000 monthly minutes

- Heavy builds: Docker images of 500MB-1GB took too long on shared runners

- Local resources: I needed to access a PostgreSQL database on my server for tests

- Cost optimization: I already had a VPS running at 30% capacity

- Custom environment: I needed specific tools (various cloud provider CLIs)

- Network speed: Direct access to local cache and private registries

However, consider self-hosted when:

- You have frequent builds and tight minute limits

- You work with monorepos or projects with long builds

- You already have servers with available capacity

- You need access to local resources (databases, internal services)

When I DON’T Recommend Self-Hosted ⚠️

Being honest is important. Self-hosted isn’t always the right solution.

I wouldn’t use it myself in these cases:

- Low usage: If you’re within free tier limits, why complicate your life?

- Simplicity first: You prefer zero maintenance? Stick with GitHub-hosted

- Security concerns: Don’t want to expose your infrastructure? Understandable

- Variable workload: Sporadic and unpredictable builds? GitHub-hosted scales automatically

- Public repositories: This is critical — anyone can fork your repo and open a pull request with malicious code that will run on YOUR server. This could lead to cryptocurrency mining, data theft, or other attacks. GitHub strongly recommends using self-hosted runners only with private repositories unless you have strict approval workflows in place.

⚠️ Security Warning: Self-hosted runners on public repositories are a significant security risk. Malicious actors can submit pull requests that execute arbitrary code on your infrastructure. Always use GitHub-hosted runners for public repos, or enable “Require approval for all outside collaborators” in your repository’s Actions settings.

A trick I learned: you can combine both approaches. I use GitHub-hosted for quick tests and self-hosted only for heavy Docker builds.

🚀 Setting Up a Self-Hosted Runner

Let’s walk through setting up a self-hosted runner. I’ll assume you have a Linux server (physical, VM, or cloud instance).

Prerequisites

Before we start, make sure you have:

# A Linux server with:

# - Ubuntu 20.04+ (or similar)

# - Stable internet connection

# - At least 2GB RAM and 20GB disk spaceNote: Docker is not required for basic runner setup. You’ll only need Docker if you plan to build container images in your workflows. We’ll cover Docker-specific workflows later in this article.

Step 1: Navigate to Your Repository Settings

- Go to your GitHub repository

- Click Settings → Actions → Runners

- Click New self-hosted runner

- Choose your OS (we’ll use Linux)

GitHub will show you the exact commands to run. Here’s the general flow:

Step 2: Download and Configure the Runner

# Create a folder for the runner

mkdir actions-runner && cd actions-runner

# Download the latest runner package

curl -o actions-runner-linux-x64-2.311.0.tar.gz \

-L https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v2.311.0/actions-runner-linux-x64-2.311.0.tar.gz

# Extract the installer

tar xzf ./actions-runner-linux-x64-2.311.0.tar.gzPro Tip: Check the GitHub UI for the latest version URL — runner versions update frequently.

Step 3: Configure the Runner

# Configure the runner (use the token from GitHub UI)

./config.sh --url https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/YOUR_REPO \

--token YOUR_RUNNER_TOKEN

# You'll be prompted for:

# - Runner name (e.g., "my-server-runner")

# - Runner group (default is fine)

# - Labels (optional, but useful for targeting)

# - Work folder (default is fine)Important: About the Registration Token

The token shown in the GitHub UI is a short-lived registration token (valid for 1 hour). This token is used only during the initial runner configuration to authenticate and register the runner with your repository or organization.

Once configured, the runner uses a different authentication mechanism (a runner token stored in the

.runnerfile) to communicate with GitHub Actions. The registration token cannot be reused after initial setup.Key points:

- The registration token expires after exactly 1 hour

- You need to generate a new token each time you configure a new runner

- The token is displayed in Settings → Actions → Runners → New self-hosted runner

- Never share or commit this token to version control

Important labels to consider:

GitHub recommends using labels to help target specific runners in your workflows. Labels allow you to route jobs to runners with specific capabilities or characteristics.

# Example with custom labels

./config.sh --url https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/YOUR_REPO \

--token YOUR_RUNNER_TOKEN \

--labels self-hosted,linux,x64,docker,my-serverDefault labels automatically assigned:

self-hosted- Identifies the runner as self-hosted (vs GitHub-hosted)- OS label -

linux,windows, ormacOS - Architecture label -

x64,ARM, orARM64

Custom labels let you add specific capabilities:

docker- Runner has Docker installedgpu- Runner has GPU capabilitiesproduction- Runner for production deploymentsstaging- Runner for staging environments

Labels help you target specific runners in your workflows (see examples in the “Using Your Self-Hosted Runner” section below).

Step 4: Install as a Service

Instead of running the runner manually, let’s set it up as a systemd service:

# Install the service

sudo ./svc.sh install

# Start the service

sudo ./svc.sh start

# Check status

sudo ./svc.sh statusThis ensures the runner starts automatically on boot and restarts if it crashes.

Step 5: Verify in GitHub

Head back to your repository’s Settings → Actions → Runners. You should see your runner listed as Idle (green dot).

🔧 Using Your Self-Hosted Runner

Now that your runner is set up, let’s use it in a workflow.

Basic Workflow Example

name: Build on Self-Hosted Runner

on:

push:

branches: [ main ]

jobs:

build:

# Use your self-hosted runner

runs-on: self-hosted

steps:

- name: Checkout code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Build project

run: |

echo "Building on my own server!"

npm install

npm run build

- name: Run tests

run: npm testTargeting Specific Runners with Labels

If you have multiple self-hosted runners, use labels to target specific ones:

jobs:

build-docker:

# Only run on self-hosted runners with 'docker' label

runs-on: [self-hosted, docker]

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Build Docker image

run: docker build -t myapp:latest .Combining GitHub-Hosted and Self-Hosted

You can use both in the same workflow:

jobs:

test:

# Fast tests on GitHub-hosted

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- run: npm test

deploy:

# Heavy deployment on self-hosted

runs-on: self-hosted

needs: test

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- run: ./deploy.sh📦 Working with Docker and GitHub Container Registry (GHCR)

This section is for users who need to build and push Docker images. If your workflows don’t involve Docker, you can skip this section. For standard use cases (building code, running tests, deploying applications), the basic setup above is all you need!

If you’re building Docker images in your CI/CD pipeline, you can use GitHub Container Registry (GHCR) with both GitHub-managed and self-hosted runners. The main difference with self-hosted runners is the authentication setup — let’s see how it changes.

Prerequisites for Docker Workflows

If you want to use your self-hosted runner for Docker-related tasks, you’ll need:

# Install Docker on your runner server

curl -fsSL https://get.docker.com -o get-docker.sh

sudo sh get-docker.sh

# Add the runner user to the docker group (if using a service account)

sudo usermod -aG docker $USER

# Verify Docker is working

docker --versionWhy GHCR?

GitHub Container Registry offers:

- Free for public packages

- Private packages included with GitHub plans

- Integrated with GitHub permissions

- Fast pulls from GitHub Actions (same infrastructure)

- No rate limiting for authenticated requests

Note: These GHCR benefits apply to both GitHub-managed and self-hosted runners!

Authentication: GitHub-Managed vs Self-Hosted Runners

The key difference when using self-hosted runners is how you authenticate with GHCR.

On GitHub-Managed Runners (Default)

GitHub-managed runners use the built-in GITHUB_TOKEN:

- name: Log in to GitHub Container Registry

uses: docker/login-action@v3

with:

registry: ghcr.io

username: ${{ github.actor }}

password: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }} # Built-in tokenOn Self-Hosted Runners (Requires PAT)

Self-hosted runners need a Personal Access Token (PAT) and your GitHub username:

- name: Log in to GitHub Container Registry

uses: docker/login-action@v3

with:

registry: ghcr.io

username: <your-github-username> # Replace with your username

password: ${{ secrets.GHCR_TOKEN }} # Your PAT tokenSetting Up PAT for Self-Hosted Runners

To use GHCR with self-hosted runners, you need to create a Personal Access Token.

Step 1: Create a Personal Access Token

- Go to GitHub Settings → Developer settings → Personal access tokens → Tokens (classic)

- Click Generate new token (classic)

- Give it a descriptive name (e.g., “GHCR Access”)

- Select scopes:

- ✅

write:packages(for pushing) - ✅

read:packages(for pulling) - ✅

delete:packages(optional, for cleanup)

- ✅

- Generate and copy the token (you won’t see it again!)

Step 2: Add Token as a Secret

- Go to your repository Settings → Secrets and variables → Actions

- Click New repository secret

- Name:

GHCR_TOKEN - Value: paste your PAT

- Click Add secret

Security Note: Never commit tokens to your repository. Always use GitHub Secrets!

Building and Pushing to GHCR

Here’s a complete example using docker/build-push-action:

name: Build and Push to GHCR

on:

push:

branches: [ main ]

env:

REGISTRY: ghcr.io

IMAGE_NAME: ${{ github.repository }}

jobs:

build-and-push:

runs-on: self-hosted # Using our self-hosted runner

permissions:

contents: read

packages: write # Required for GHCR

steps:

- name: Checkout repository

uses: actions/checkout@v4

# Set up Docker Buildx for advanced build features

- name: Set up Docker Buildx

uses: docker/setup-buildx-action@v3

# Log in to GHCR using PAT (required for self-hosted runners)

# Note: GitHub-managed runners can use secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN and github.actor

- name: Log in to GitHub Container Registry

uses: docker/login-action@v3

with:

registry: ${{ env.REGISTRY }}

username: <your-github-username> # Replace with your GitHub username

password: ${{ secrets.GHCR_TOKEN }}

# Extract metadata for tagging

- name: Extract Docker metadata

id: meta

uses: docker/metadata-action@v5

with:

images: ${{ env.REGISTRY }}/${{ env.IMAGE_NAME }}

tags: |

# Tag with branch name

type=ref,event=branch

# Tag with commit SHA

type=sha,prefix={{branch}}-

# Tag as 'latest' for main branch

type=raw,value=latest,enable={{is_default_branch}}

# Build and push Docker image

- name: Build and push Docker image

uses: docker/build-push-action@v5

with:

context: .

push: true

tags: ${{ steps.meta.outputs.tags }}

labels: ${{ steps.meta.outputs.labels }}

# Use local cache for faster builds

cache-from: type=local,src=/tmp/.buildx-cache

cache-to: type=local,dest=/tmp/.buildx-cache-new,mode=max

# Rotate cache to prevent unlimited growth

- name: Move cache

run: |

rm -rf /tmp/.buildx-cache

mv /tmp/.buildx-cache-new /tmp/.buildx-cacheUnderstanding the Workflow

Let’s break down the important parts:

Docker Buildx

- name: Set up Docker Buildx

uses: docker/setup-buildx-action@v3Buildx provides:

- Multi-platform builds (amd64, arm64, etc.)

- Advanced caching for faster rebuilds

- Parallel builds for multi-stage Dockerfiles

Metadata Action

- name: Extract Docker metadata

id: meta

uses: docker/metadata-action@v5

with:

images: ${{ env.REGISTRY }}/${{ env.IMAGE_NAME }}

tags: |

type=ref,event=branch

type=sha,prefix={{branch}}-

type=raw,value=latest,enable={{is_default_branch}}This creates intelligent tags:

ghcr.io/username/repo:main(branch name)ghcr.io/username/repo:main-abc1234(branch + SHA)ghcr.io/username/repo:latest(only for main branch)

Build and Push

- name: Build and push Docker image

uses: docker/build-push-action@v5

with:

context: .

push: true

tags: ${{ steps.meta.outputs.tags }}

cache-from: type=local,src=/tmp/.buildx-cache

cache-to: type=local,dest=/tmp/.buildx-cache-new,mode=maxKey features:

push: true: Actually pushes to registry (omit for testing)cache-from/to: Dramatically speeds up rebuilds on self-hosted runnersmode=max: Aggressive caching for maximum speed

🔐 GHCR vs Docker Hub: Key Differences

If you’re coming from Docker Hub, here are the main differences with GHCR:

| Feature | Docker Hub | GHCR |

|---|---|---|

| Image URL | docker.io/user/image | ghcr.io/user/image |

| Authentication | Username + Password/Token | GitHub username + Token (PAT for self-hosted, GITHUB_TOKEN for managed) |

| Permissions | Separate system | Integrated with GitHub |

| Rate Limits | 100 pulls/6h (anonymous), 200 pulls/6h (free) | No limits (authenticated) |

| Private Images | 1 free repo, then paid | Included with GitHub plan |

| Integration | Manual setup | Native GitHub Actions support |

Pulling from GHCR on Your Server

To pull images from GHCR on your self-hosted runner or any other server:

# Log in to GHCR

echo $GHCR_TOKEN | docker login ghcr.io -u USERNAME --password-stdin

# Pull the image

docker pull ghcr.io/username/repo:latest

# Run it

docker run -d ghcr.io/username/repo:latestUsing in Docker Compose

services:

app:

image: ghcr.io/username/myapp:latest

# ... other configBefore running docker-compose up, make sure you’re logged in:

docker login ghcr.io -u USERNAME -p $GHCR_TOKEN

docker-compose up -d🛡️ Security Considerations

Running self-hosted runners comes with security responsibilities. Here’s what you need to know.

1. Isolation is Critical

Problem: Self-hosted runners can access your local network and resources.

Solution:

# Run runner in a container or VM

docker run -d \

--name github-runner \

--restart unless-stopped \

-v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock \

your-runner-image:latestOr use ephemeral runners that are destroyed after each job.

2. Be Careful with Public Repositories

Problem: Anyone can fork your public repository and open a pull request containing malicious code that will execute on your self-hosted runner. This is a critical security risk.

Real-world risks:

- Cryptocurrency mining using your server’s resources

- Data exfiltration from your network

- Installation of backdoors or malware

- Use of your runner as a proxy for attacks

- Access to secrets and environment variables

GitHub’s official recommendation: Do not use self-hosted runners with public repositories unless you have strict security measures in place.

Solutions:

- Best practice: Only use self-hosted runners for private repositories

- If you must use them on public repos:

- Enable “Require approval for all outside collaborators” in Settings → Actions → General

- Carefully review every pull request before approving workflow runs

- Use ephemeral runners that are destroyed after each job

- Run runners in isolated environments (containers/VMs) with no access to sensitive resources

⚠️ GitHub Security Advisory: “We strongly recommend that you do NOT use self-hosted runners with public repositories. Forks of your public repository can potentially run dangerous code on your self-hosted runner machine by creating a pull request that executes the code in a workflow.” — GitHub Docs: About self-hosted runners

3. Secrets Management

Never hard-code secrets:

# ❌ WRONG

- run: docker login -u myuser -p mypassword

# ✅ CORRECT (for self-hosted runners)

- run: echo "${{ secrets.GHCR_TOKEN }}" | docker login ghcr.io -u <your-github-username> --password-stdin4. Network Security

Consider firewall rules:

# Only allow outbound connections to GitHub

sudo ufw allow out to github.com

sudo ufw allow out to ghcr.io

# Block all other outbound by default

sudo ufw default deny outgoing🎛️ Advanced: Multiple Runners for Scaling

Need more capacity? Run multiple runners on the same or different machines.

Same Machine, Multiple Runners

# Create separate directories

mkdir ~/actions-runner-1

mkdir ~/actions-runner-2

# Configure each with different names

cd ~/actions-runner-1

./config.sh --url ... --name runner-1

cd ~/actions-runner-2

./config.sh --url ... --name runner-2

# Install both as services

sudo ~/actions-runner-1/svc.sh install

sudo ~/actions-runner-2/svc.sh installAuto-Scaling with Runner Groups

For enterprise needs, consider:

- Actions Runner Controller (ARC): Kubernetes-based auto-scaling

- Terraform: Infrastructure as Code for runner provisioning

- Cloud auto-scaling: Spin up runners on-demand

📊 Monitoring Your Runners

Keep an eye on your runners’ health and performance.

Check Runner Status

# View systemd service status

sudo systemctl status actions.runner.*

# View runner logs

sudo journalctl -u actions.runner.* -fMonitor Resource Usage

# Install monitoring tools

sudo apt install htop

# Watch resource usage

htop

# Or use docker stats if running in containers

docker stats github-runnerGitHub UI Monitoring

In Settings → Actions → Runners:

- ✅ Green dot: Runner is idle and ready

- 🟡 Yellow dot: Runner is currently running a job

- ⚫ Gray dot: Runner is offline

💡 Tips and Best Practices

From my experience running self-hosted runners, here are some lessons learned:

1. Use Labels Wisely

# In config.sh

--labels self-hosted,linux,x64,docker,production,gpu

# In workflow

runs-on: [self-hosted, gpu] # Only runs on runners with GPU2. Clean Up Docker Images

Self-hosted runners can accumulate Docker images quickly:

# Add to cron (weekly cleanup)

0 0 * * 0 docker system prune -af --volumesOr add as a workflow step:

- name: Clean up Docker

if: always()

run: docker system prune -f3. Keep Runners Updated

# Check for updates

cd ~/actions-runner

sudo ./svc.sh stop

./config.sh remove

# Download latest version

# Reconfigure and restartOr use a container-based runner that you can update by pulling a new image.

4. Use Ephemeral Runners for Untrusted Code

# Configure as ephemeral (auto-deregisters after one job)

./config.sh --url ... --token ... --ephemeralThis is great for:

- Public repositories

- Pull requests from forks

- Maximum isolation

🎬 Conclusion and Personal Reflections

After months of using my self-hosted runner, I can say it was one of the best decisions I made for my projects.

What I’ve Learned

The advantages I’ve personally experienced:

- Real savings: Since using the runner, I haven’t come close to the 2,000-minute limit. Zero additional costs

- Faster builds: My Docker images now build in 3-4 minutes instead of 8-10. Local cache makes a huge difference

- Flexibility: I can install any tool I need without depending on what GitHub offers

- Control: Direct access to databases and local services for integration tests

But it’s not all roses:

There were moments when I thought “maybe GitHub-hosted was simpler”:

- Maintenance responsibility: You must regularly update the runner software, OS patches, and security updates — GitHub doesn’t do this for you

- Disk space management: You need to monitor disk space manually and clean up old builds/caches

- Availability: If your server goes down, your workflows don’t run (no SLA guarantees)

- Security burden: You’re responsible for securing the runner, managing access, and protecting against malicious code

- Initial setup: Requires some patience and Linux server knowledge

My Practical Advice

Use self-hosted if:

- You do many builds per day (> 10-15)

- You already have a server with available resources

- You like having control over the environment

- Your builds are heavy (Docker, compilation, monorepo)

DON’T use self-hosted if:

- You’re just starting a project (use GitHub-hosted first and see if you need it)

- You don’t have Linux server experience

- You work mainly on public repos (security risk)

- You prefer simplicity over customization

The middle ground I use:

In my main workflow I have both GitHub-hosted and self-hosted:

- Quick tests → GitHub-hosted (ubuntu-latest)

- Docker builds and deploy → Self-hosted

This way I get the best of both worlds.

What to Check Before Using Self-Hosted

Before diving in, verify:

- Real costs: Calculate if the server cost is less than the GitHub plan you’d need to subscribe to

- Server capacity: Monitor CPU, RAM, and disk during a few builds to see if your server can handle it

- Connectivity: A server with unstable connection is worse than GitHub-hosted

- Security: Make sure you understand the security implications (especially for public repos)

- Maintenance time: Are you willing to dedicate 30 min per month for maintenance?

When I DON’T Recommend It

There are situations where I strongly advise against self-hosted:

Very popular public repositories: If you receive many PRs from external contributors, someone could exploit your runner for cryptocurrency mining, data theft, or other malicious purposes. GitHub’s official documentation explicitly warns against using self-hosted runners with public repositories due to the risk of arbitrary code execution from pull requests.

Critical projects without backup: If your server is a single point of failure and you have no alternatives, use GitHub-hosted which has guaranteed SLAs.

Teams without DevOps experience: If nobody on the team knows how to manage Linux servers, troubleshooting, monitoring… better avoid it.

Compliance and audit: If you work in environments with strict compliance requirements, GitHub-hosted offers better certifications and audit trails.

What to Do If You Need Temporary Runners

A trick I discovered later: ephemeral runners.

If you need runners for a limited period or for testing:

# Configure as ephemeral (auto-deregisters after one job)

./config.sh --url ... --token ... --ephemeralUseful for:

- Testing new configurations

- One-off builds

- Maximum security (runner is destroyed after each job)

I use them when I need to test new configurations before putting them on permanent runners.

📚 Resources

- GitHub Actions Self-Hosted Runners Documentation

- GitHub Container Registry Documentation

- Docker Build Push Action

- Docker Buildx Documentation

- Actions Runner Controller (ARC) - For Kubernetes auto-scaling

Related articles on my blog:

- How I built this blog with Astro and CI/CD - If you want to see how I use runners to automatically deploy this blog

Thanks for reading! If you have questions or want to share your self-hosted runner setup, feel free to reach out. I’d love to hear how you implemented it!

Related Articles

How I Built This Blog: Astro, Docker Images, Caddy and Zero-Touch CI/CD

November 24, 2025

The complete story of building my personal blog with Astro's versatility, Caddy instead of Nginx, Docker containerization, and GitHub Actions for automated deployments.

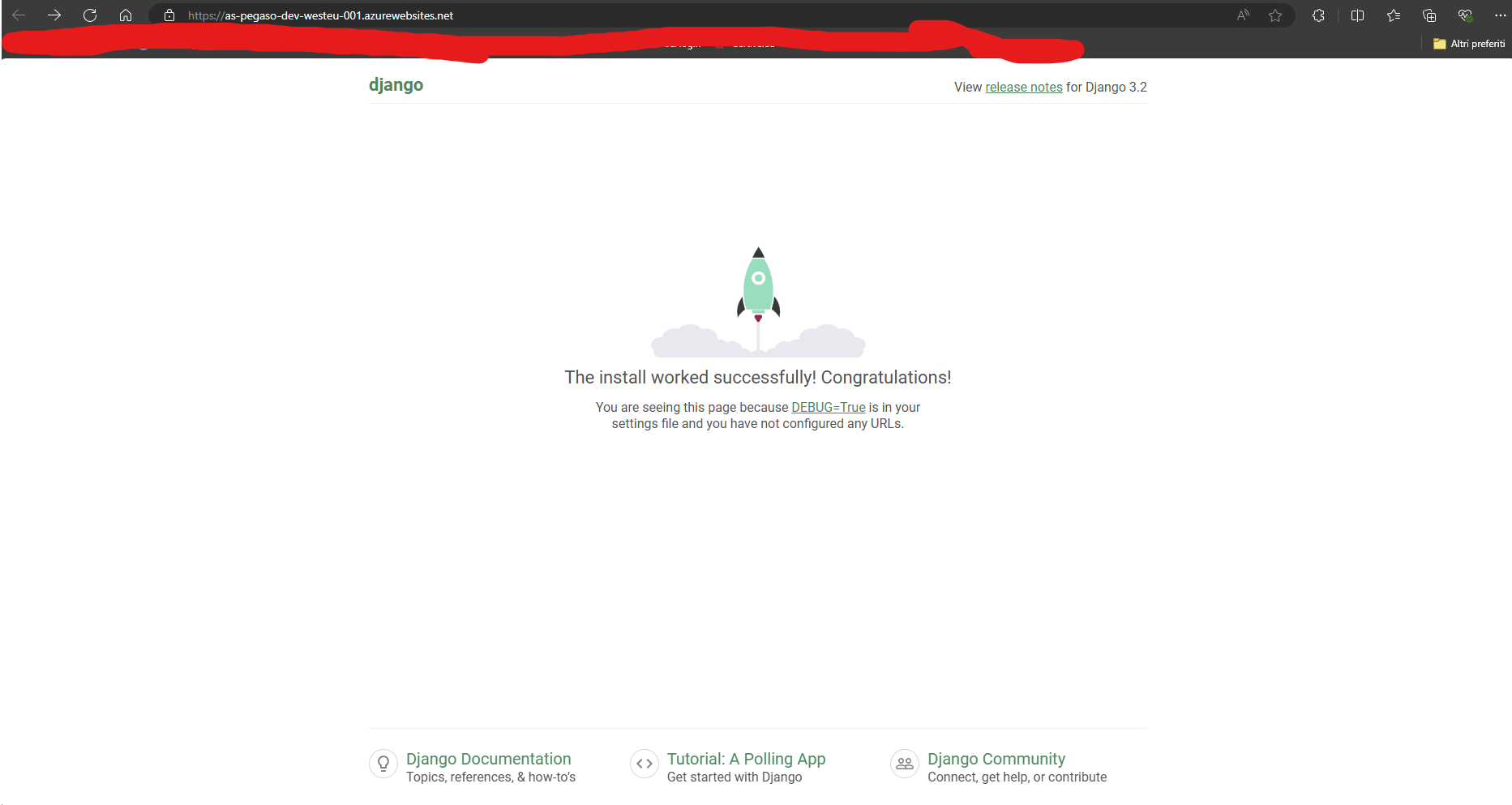

Building a Django Hotel Booking System - Part 2: Cloud Deployment on Azure

November 22, 2024

Deploy a Django application to Azure using Infrastructure as Code with Terraform, CI/CD pipelines with GitHub Actions, and modern DevOps practices for zero-touch deployment.

Building My Homelab: From Failed Attempts to a Solid Proxmox Setup

December 28, 2025

After years of failed attempts, I finally built a stable homelab using Proxmox, LXC containers, and proper architectural decisions. Here's my journey from chaos to a manageable self-hosted infrastructure.

Contattami

Hai domande o vuoi collaborare? Inviami un messaggio!